Service Design for Waste Management

Driven by Wu Xing, Service Design Transforms a Chinese Firm

The Vice Chairman, Jin Duo was frustrated, the hightech waste-management company she had been successfully running for more than a decade was seeing troubles with speeding up growth. Now known as Grandblue Environmental Co. Ltd., a publicly listed, state-controlled shareholding company with good technology, solid management and a steady customer, the Government, which was encouraging Grandblue to expand into more regions across China to help tackle waste management. However, even with high demand, local communities near newly planned plant locations, protested and said, “No, not in my backyard!”, a challenge GrandBlue came to ChinaBridge for support.

Based in Foshan, Guangdong province, Grandblue carries out water purification, sewage treatment and solid-waste recycling and gasification. The company processes some 20 million kilos a year of waste from 17 million people. A couple of years ago, despite having done nothing wrong, it suffered from the stigma of being a firm that handles waste and rubbish, earning the association that it was dirty and maybe even toxic. Local communities had no interest in welcoming Grandblue as a neighbour.

I met Jin in 2015, and learned of her dilemma in trying to grow the company. She’s an impressive woman. Not only was she operating in an industry run almost entirely by men, but she also came from outside the industry and brought an open mind and a fresh perspective.

She had joined Grandblue — then known as Nanhai Development Co. — in 2004, after having studied finance and economics, and had built a CV in senior management positions in various industries.

Grandblue’s challenge intrigued me, and I thought that perhaps my Shanghai-based strategic innovation firm, CBi China Bridge, could help. Jin was willing to listen.

CBi has been active in service design for many years, including organising “service design jams” since 2011, with the aim of promoting the design discipline within China. But we have encountered many hurdles.

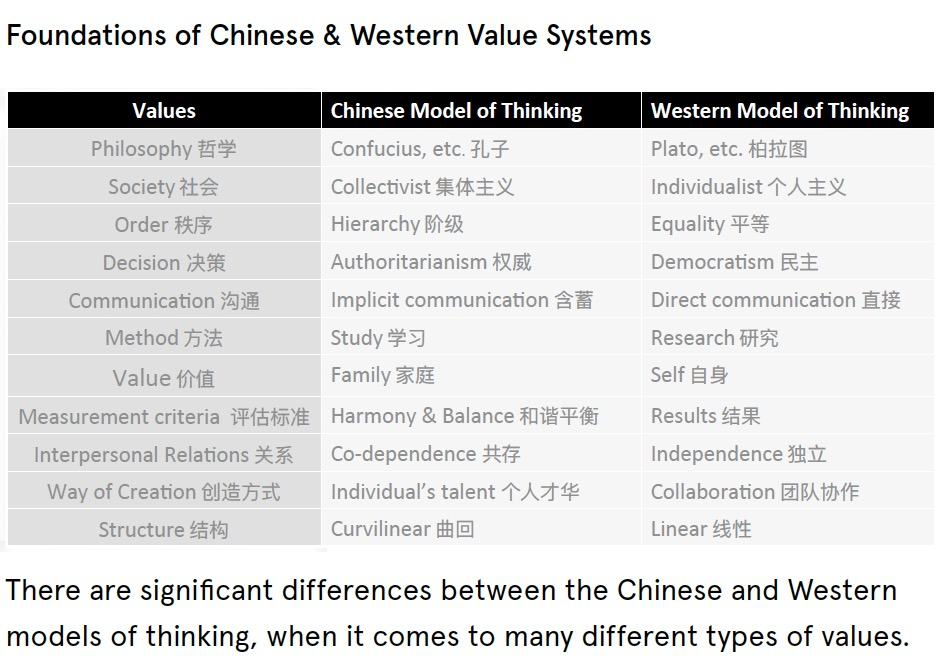

In China, very few decision makers became involved in our efforts, because they didn’t understand the value of what we were doing. We then tried to apply a Western version of service design, but it didn’t go well. Industry engagement in China is at a lower level, and the decision makers often just don’t care. The leaders of most large enterprises – especially those that are state-owned – think “design is not my thing.”

That got us wondering what we could do to break through these barriers. We realised that we needed to start with cultural change and mindset change within these organisations, instead of with service design. We discovered that once the culture and mindsets change, then the budgets will come, and service design is the deliverable.

On top of that, the timing for such an approach seemed right. The government had launched a “Made in China 2025” initiative, the country’s most comprehensive and ambitious industrial plan to date, to upgrade China’s manufacturing economy. Beijing had declared that it wants to see China, with its 1.4 billion people and $11 trillion economy, shift from beingan industrial powerhouse to a service powerhouse.

In its mission to promote service-oriented manufacturing and manufacturing-related service industries, the government had outlined nine key tasks on which to focus. These include:

— Improving manufacturing innovation

— Strengthening the industrial base

— Enforcing “green” (or more sustainable) manufacturing

— Advancing the restructuring of the manufacturing sector

— Internationalising manufacturing

— Integrating information technology and industry

— Fostering Chinese brands, and

— Promoting breakthroughs in ten key sectors

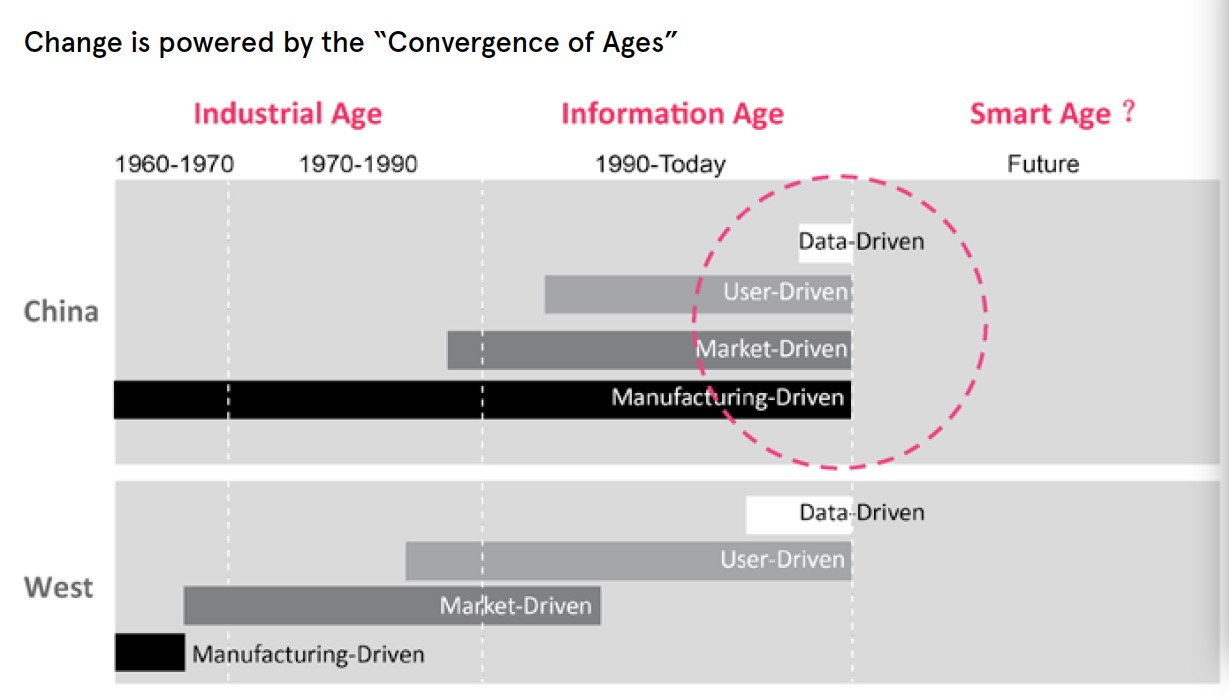

During the “convergence of ages” — from the current ‘Information Age’ potentially to a more data-driven ‘Smart Age’ — we believe that service design is a good bridge to help transform China’s traditional industries and businesses. The aim is to shift from simply making goods, to delivering a service that provides goods.

But executing such change is never easy. A recent McKinsey global leadership study indicates that only 30 percent of companies succeed in significantly transforming themselves. In addition, according to an IBM study, the biggest hurdles to such change are not budgetrelated, but rather involve changing mindsets and corporate culture. And there is no doubt that in China, when it comes to service design, there are significant gaps in both mindsets and culture among traditional businesses.

Over the past several years I had been developing a theory based on Wu Xing —五 [wˇu] 行 [xíng], a traditional Chinese philosophy that has existed for thousands of years. Wu Xing focuses on the interrelationships of the five elements:

Enhancing

— Wood feeds Fire;

— Fire creates Earth (ash);

— Earth bears Metal;

— Metal collects Water and

— Water nourishes Wood.

Diminishing

— Wood parts Earth;

— Earth absorbs Water;

— Water quenches Fire;

— Fire melts Metal and

— Metal chops Wood.

I started wondering if this concept could be applied to business. We used the Wu Xing framework to identify five interrelated organisational elements impacting service design:

— Strategy

— Leadership

— Culture

— Creativity

— Data

We’ve been developing our working philosophy – a combination of our Chinese culture with a Western toolbox. We find that it is very powerful. The interrelationship is as follows: Strategy empowers Leadership; Leadership encourages Culture; Culture will generate Creativity; Creativity generates Data (which is the business result); and Data helps to improve the Strategy.

For example, organisations need a defined, clear strategy, but that strategy must not be so strong and rigid as to restrict creativity. And if the culture is too strong, it can blind one to the data that reveals different needs. We need to know when and where to let big ideas grow in an organisation, while being careful to not allow overly bold ideas to disrupt the strategy. Everything is interrelated and requires a careful balance.

That brings us back to Grandblue, which serves as case study of how we can apply service design using a holistic approach to bridge East and West. Jin agreed to allow us to apply these principles in her company. In the waste management sector, securing positive community engagement was the key to the company’s potential growth. But how could it be achieved?

We suggested that Grandblue needed to shift its business model from “B2G” (business-to-government) to “B2G+C” (business-to-government, plus community) model. The public had to learn and accept that the company had state-of-the-art technology, strong environmental safeguards, and a sincere interest in the welfare of the local communities where they operated.

Making this happen took many forms. Grandblue began using white trash hauler trucks to reinforcetheir cleanliness (such trucks in China typically are blue). They completely rebuilt their main production compound in Foshan using very modern, futuristic architecture that looks like anything but a waste management plant. And they rebranded themselves as an “integrated environmental service leader”.

But all of this was still only the start. We began working with the company to change its internal culture. We wanted to help them to stimulate “bottom-up innovation”. Our goal was to create an external impact through internal changes, because without internal change, nothing would happen.

By helping them identify and select “creative stars” among their different departments, we could more effectively implement design thinking tools and collaboration workshops to support for problem solving, idea generation and to create a stronger community, internally and externally.

After that, we also worked with those stars to build internal systems and mechanisms, allowing them to apply service design thinking to their innovation projects.

One of the key results of this employee brainstorming and co-creation process was the decision for Grandblue to build its own theme park, on property adjacent to its Foshan plant. The park is under construction now, and is due to open in the second half of 2017.

Located in the center of Grandblue Industrial Park, the interactive theme park will cover about 20,000 square meters. It’s designed for general public, mainly targetet at children aged between 6 and 17 years old, and will allow visitors to follow a route through Grandblue’s production area, an exhibition hall and the park grounds, all of which will be linked by a physical “passport” that lists several tasks to be done. Each task corresponds to a key message that is environment-related. All activities are aimed to help children — through hands-on exploration — gain a better understanding of the benefits of such things as recycling, saving energy and overall conservation.

Chinese media have dubbed the project “an environmental-themed Disneyland,” while noting it is the first theme park in the country to focus on environmental protection.

Even without the theme park being completed yet, Grandblue already has begun implementing various other aspects of the service program that CBi designed for them. This includes open monitoring, whereby the public is welcome to visit the plant at any time. The company has increased its involvement in social media, opened an online store, and launched a local education program with neighbouring elementary schools, to teach children what it means in their daily lives to save energy, and how to use waste materials to create useful things, such as sculptures or souvenirs.

Previously the community always protested that it was not good to have a waste management plant next to the school, and a physical wall separated the Grandblue facilities in Foshan from the school next door. That school has since decided to tear down the wall.

When the company first tried to build a new plant in Fujian, the local community there protested. Then Grandblue invited those affected to visit their plant in Foshan. Those visitors were so impressed that they recently told their local government that only Grandblue is allowed to build a waste management factory in their city! That’s the power of using community to impact government decision making.

Grandblue now has expanded across China, and owns several factories in seven provinces.

In the meantime, we have broadened our engagement with the company on various levels. They decided to continue with our culture-change and innovation-capability building program throughout the next year, and further employ us in 2017.

As part of a million-dollar project, we have done ten workshops with employees in different subsidiaries, and developed both a “train the trainer” programme for them internally, and a leadership development program. It’s become an innovation initiative through - out their whole group.

The Grandblue employees love CBi very much. They treat us as their mentor and as their teacher, empowering them to be more creative and happier in their work environment. They viewed these changes as being generated by themselves, and they were eager to implement them.

We started this whole project back in November 2015 by understanding their strategy, and being empowered by their leader. But we really started by reshaping the internal culture. The reinvigourated culture generated a lot of ideas. We then integrated the ideas, and used our professional tools and methods for service design. Part of the result is the theme park. But the real result is the business model innovation.

This is the power of service design.